Part 4 of 4 in the CompetencyCore™ Guide to 360 Multi-source Feedback series:

By Ian Wayne, M.Sc and Suzanne Simpson, PhD, C. Psych.- Feedback Goals

- Process and Resources

- Delivering the Project

- Selecting a multi-source feedback software solution

The first three blogs in this series examined “best practices” in establishing the goals for, designing and implementing a 360 Multi-source Feedback process. However, it is almost impossible to implement an effective Multi-source Feedback process without having a software system in place to support delivery and analysis of the Feedback results.

This post examines what to look for in selecting a software system that will work for your organization.

Why a competency management software system is important

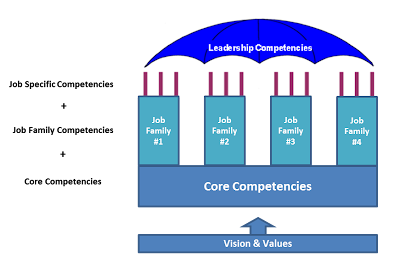

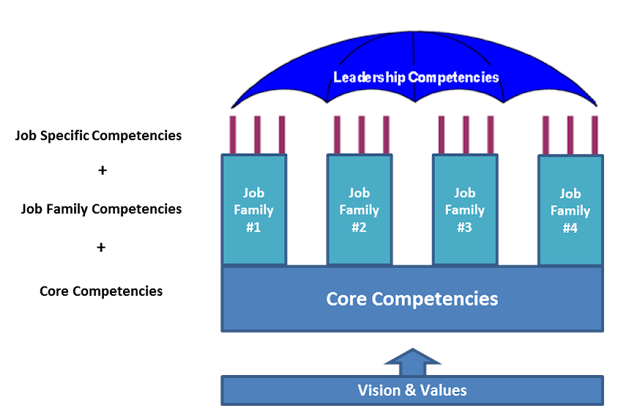

Designing, developing, implementing and maintaining a competency framework is difficult to do in a paper-based format. It can quickly become unwieldy and out of control if not managed through a competency management software system.

Without such a system it is difficult to build and maintain processes like 360 Multi-source Feedback based on the most current competency information.

What to look for in a system

- A system with existing well-researched competency content

This includes a library of the general competencies as well as technical / professional competencies that are suited to your organization. These days, it is not necessary or even advisable to develop your competencies from scratch. It can take years to develop high-quality competencies.

Vendors often also have standard job competency profiles available that reflect the job duties / tasks typically required in jobs within specific functional areas as well as industry sectors. These can then become the starting point for use within your organization, editing and adjusting them to fit the unique requirements of your organization. - A system that supports standardized implementation

Organizations are increasingly experiencing distributed workplaces, with employees operating out of multiple locations. As a result, it is becoming more difficult to ensure that the human resource processes are implemented in a uniform and standardized way. If you have a system that supports the standardized adoption of competency content and competency-based HR processes, it becomes easier to ensure that HR professionals, managers and employees are accessing and implementing the correct competency content in an online 360 Multi-source Feedback process. - A flexible system configurable to your needs

In many 360 Multi-source systems, the software delivery and content are inextricably linked. Organizations therefore have to “buy-in” to the content and underlying model being delivered in the software. So, for example, if you wish to implement a 360 process to assess Leadership Competencies, you effectively have to adopt the leadership competency model that is part of the feedback tool. But the model being delivered in the software may not meet your organizational needs, reflect the values and culture of your organization, or incorporate the competencies you are attempting to reinforce and develop within your various employee groups.

A more appropriate and valid approach is to have a system that links to the competency content and models you have designed and developed for your organization. As such, the system should allow you to pick from a list job competency profiles or models, and then implement this competency information within the 360 Multi-source Feedback tool that is part of the same system.

In addition, the tool should allow you to select the individuals and groups who will be part of the feedback process. In some cases, for example, you may wish to collect feedback from work colleagues; in other cases you may wish to collect feedback from work colleagues and clients of the target participants. In each case, the groups providing feedback should be based on the job being performed and the purpose of the assessment.

The system should also be flexible with regard to the rating scale being implemented, both in terms of the number of levels (rating scales can run anywhere from 3 to 7 levels) as well as the scale type (e.g., effectiveness scale; observed frequency of the behaviour; etc.). Research on the number of levels and type of rating scale is extensive and subject to a great deal of debate as to what is best practice. You should have the flexibility to be able to choose or design a rating scale that works best for the feedback process and type of work being performed.

Finally, you should have the flexibility to identify what type of competency information is being assessed. Most systems take the assessment process down to the level of the behaviour / performance indicators for each competency (e.g., for Client Focus – proficiency level 3 – “Looks for ways to add value beyond the client’s immediate request”), but in some cases the assessment may be performed at the level of the competency. You should be able to choose what is being assessed according to the goal of the assessment. In CompetencyCore, for example, you have the choice of assessing the competencies at the individual behavioural indicator and / or at the Competency level. - Reporting of Feedback Results

The 360 Multi-source Feedback tool should also provide good graphical information that allows the comparison of results across the different types of people providing the feedback. The breakdown of information should not only be provided at the competency level, but also at the level of the individual behavioral indicators for each competency. This allows the target participant to gain different perspectives on his / her performance. It also provides a more diagnostic perspective on how each competency should be developed. For example, although the average performance on a particular competency might meet performance expectations, individual behaviours may require improvement within the competency.

Finally, organizations can engage in a 360 Multi-source Feedback process to review performance at an organizational, regional, and / or functional level (e.g., all financial jobs). The reporting tools should therefore allow for the aggregation of data to determine key themes across selected groups. Plans and programs can then be identified to address high-priority development or training needs. - Security, Confidentiality and Anonymity

As noted in a previous post, it is important to protect the anonymity of certain types of raters – in particular, when using direct reports to the target participant in the Feedback process. As well, with a small number of raters, one person’s feedback can have a disproportionate impact on the overall ratings. It is therefore important to be able to define the rules in the software for combining certain types of raters’ scores to ensure feedback confidentiality and anonymity.

Finally, when raters are asked to provide comments to substantiate their ratings, it is important that they are instructed to do this in a positive and helpful way, and that when doing so, they abide by whatever confidentiality and anonymity rules your organization establishes. Make sure that your software allows you to incorporate these kinds of instructions. - Integration and Alignment within the Talent Management Process

360 Multi-source Feedback is not a stand-alone process. It is done to accomplish a particular goal, for example to address gaps in competency through learning and development. Therefore, the software should allow the user to link to other HR processes in the system. For example, in CompetencyCore, any competency gaps identified through the assessment process can feed directly into a Learning Plan tool that provides targeted learning resources (e.g., on-job activities, books, courses, etc.), organized by competency, to help address those gaps. This is only one example of how the 360 Feedback process can be integrated with, and feed into, other Talent Management processes within the organization.

Sources:

DTI. (2001). 360 Degree Feedback: Best Practice Guidelines. Downloaded from: www.dti.gov.uk/mbp/360feedback/360bestprgdlns.pdf

Maylett, T. (2009). 360-Degree Feedback Revisited: The Transition From Development to Appraisal. Compensation & Benefits Review, 41(5), 52–59.

Morgeson, F. P., Mumford, T. V., & Campion, M. A. (2005). Coming Full Circle: Using Research and Practice to Address 27 Questions About 360-Degree Feedback Programs. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 196–209.

Want to learn more? Get the Guide!

This guide reviews the best practices for 360 degree feedback, beginning with establishing 360 feedback goals, to process design, project delivery and software platform selection. It also includes a 360 degree feedback checklist for a successful implementation.